|

| National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute |

But N.G. was a comedian who dished out wisecracks and snarky comments. Everyone knew he was sick. What we didn’t know was how serious his illness really was. For the first two years of high school, we barely saw him. It seemed like weeks turned into months before he returned to school. And it wasn’t until his last year or two in school that we saw him more frequently. Then, on June 2, 2010, one year after we graduated, N.G. died.

When I saw the news on Facebook that he’d passed away, I had a flashback of a conversation with my principal.

I was in the his outer office talking with the secretary, when I saw N.G. stroll in, grab a soda from the principal’s mini refrigerator and then walk back out. I couldn’t believe it. I went into principal’s inner office to get a closer look at the just-raided refrigerator. Then I stared at the principal until he looked up from his desk. “How can I help you?” he asked.

At that time, I had a smart mouth, but I was never disrespectful. “Are you kidding me?” I replied. “Didn’t you just see that? N.G. just walked in, grabbed a soda and left. If I did that, you would have probably given me detention for days!”

The principal quietly stared at his computer seemingly oblivious to what I’d just said. Without glancing up, he told me to close his office door a little and have a seat. My principal was the type to give long lectures, so I prepared myself for the worst. Well, I thought, at least I’ll be excused from being late to class this time.

After a minute the principal looked up from his computer and said, “Kareema, let me explain something to you.” At that moment, I thought I was about to be bored to death and I was wishing I’d just kept my mouth shut. But as it happened, I was grateful for the talk. The principal explained to me the reason behind N.G.’s special treatment: N.G. had sickle-cell anemia, and it was often a life-threatening disease.

The principal had been in charge of my predominantly African-American and Hispanic school for years. During that time, he said, he’d met only four students with sickle-cell disease. The first student he encountered was just like N.G. He always said he was in pain and always asked to sit in the main office. Unaware of the seriousness and suspecting the student was faking it, my principal sent the boy to class. That student died before he could graduate. In retrospect, the principal felt he should have taken the boy’s illness into consideration. He wanted another chance to redeem himself.

He got that chance when he faced three other students, including my classmate, who had sickle cell. The principal said that his heart was a little softer for these three special students because he understood how serious the disease was and how a young life could be lost so quickly before it was even given a chance to start. My principal told me that he liked to make N.G. feel like he was “the big man,” because he wasn’t sure how long he would live and felt that he deserved special treatment.

As I replayed that talk with the principal, another memory flashed into my head. It was graduation day, the last time I saw N.G. before his funeral.

During the graduation ceremony, we all had to observe one important rule: No one could clap until the last student’s name was called. But when N.G.’s name was called, my classmates and I clapped and screamed for him. The expression on my teacher’s face was classic. But after a short second, it was clear he understood why we were clapping. He didn’t reprimand us; instead, he waited for us to quiet down so N.G. could receive his diploma.

Even though it felt good to break the rules and get on my teacher’s nerves, it felt even better to see N.G. come so far. It felt amazing to realize how much we all matured over the course of four years. As people, we’d become more considerate and understanding. It was an unexplainable moment. We knew about N.G.’s struggles and, willing to face the consequences of our disruptive behavior, we’d stood in unison to applaud him. That moment was one of the highlights of my graduation day.

When I learned of N.G.’s death, I thought that he’d at least made it through one milestone in his life. As I’d continued reading the Facebook posts acknowledged his death, I became motivated to research sickle-cell disease. All I knew about the illness at the time was that it was a disease that affected African Americans and caused a lot of pain. But I wanted a better understanding of the condition.

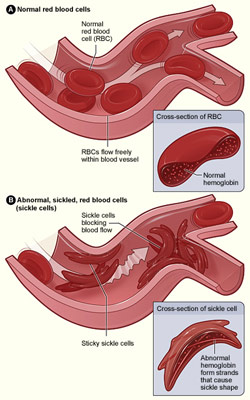

When I went online, I saw a few diagrams comparing normal donut-shaped red blood cells with sickle-shaped ones. These sickle-shaped cells would get stuck in small blood vessels and slow down or block the blood flow and oxygen to parts of the body. This blockage causes excruciating pain most commonly in the hands, feet, belly, back and chest. I also learned that sickle-cell anemia affected more African Americans and other people of color because their ancestors lived in tropical and sub-tropical regions where malaria is or was common—the sickle-cell trait helped protect against malaria. (About one in every 500 African-American newborns in the United States have sickle-cell anemia.) This knowledge allowed me to intellectually understand the problem. But I could only imagine the pain N.G. actually felt.

Back on Facebook, one of N.G.’s cousin’s created a community RIP page so everyone could say their last good-byes. It was great to read comments from classmates I knew, and I was surprised to learn N.G. affected so many other students. On the community page were details of the funeral and an announcement that all donations would go to a sickle-cell foundation.

A former classmate and I traveled to Brooklyn for N.G.’s funeral. I was shocked to see the turnout. A large number of students attended, in addition to faculty and staff members.

As I looked at my former classmate in the open casket, I thought there was a look of peace and happiness on his face. Perhaps N.G. was happy to know that all of his friends and family from different states came to say their farewells. Then again, maybe he was simply glad the suffering was over. I certainly hope he found peace, and I know that I’ll always be grateful for the life lessons he imparted on us all.

Comments

Comments